Analysis of the 2015 survey:

FOREST HEALTH BIOTECHNOLOGIES: WHAT ARE THE DRIVERS OF PUBLIC ACCEPTANCE

Prepared By Adam Koranyi, CUNY Distinguished Professor Emeritus, 10/3/2018

Note: The following is an analysis of the results from a 2015 survey conducted by Mark Needham at Oregon State University on public acceptance of genetically engineered trees. In the survey report linked above, Needham concludes that the survey demonstrates general public support for genetic engineering of trees in certain circumstances–particularly the GE American chestnut tree. The following is an analysis of the survey and its conclusions written by Adam Koranyi, Professor Emeritus of the City University of New York. Note particularly Koranyi’s flag of the role of the Forest Health Initiative in “framing the whole study, formulating the questions, etc.”

The founding of FHI was a collaborative effort between Duke Energy, the U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities and the USDA Forest Service. It views its role as supporting research on GE trees and working with regulatory agencies to remove the barriers to their environmental release. The FHI promotes the claim that GE trees will not pose a threat, and that effective GE tree research requires their release into natural environments. FHI’s policy document says, “Genes that are similar in function, have been well studied and have a strong basis to assume they will cause limited perturbations, could be allowed to be tested in GM trees in natural environments. Additionally, the FHI supports research into the GE AC as a “test tree” for the regulatory system in the U.S. and over 2009-2010 provided grants of more than $1-million to GE American chestnut research as part of a multi-institutional grant totaling $5.2-million.

This is more like an advertising brochure than a serious statistical study. One gets this impression already from its appearance: Very large print, colorful graphics, largely irrelevant illustrations (probably quite expensive). The contents quickly confirm this impression. The title says the study is about the drivers of “public” acceptance of biotechnologies. In the “project objectives” it is the “public and experts”, the experts coming from business, industry, NGO-s and academia (no indication how chosen). On page 6 (“project phases”) we learn that “experts” (under the sponsorship of the Forest Health Institute, a “government-university-industry partnership”) were framing the whole study, formulating the questions, etc.

This is more like an advertising brochure than a serious statistical study. One gets this impression already from its appearance: Very large print, colorful graphics, largely irrelevant illustrations (probably quite expensive). The contents quickly confirm this impression. The title says the study is about the drivers of “public” acceptance of biotechnologies. In the “project objectives” it is the “public and experts”, the experts coming from business, industry, NGO-s and academia (no indication how chosen). On page 6 (“project phases”) we learn that “experts” (under the sponsorship of the Forest Health Institute, a “government-university-industry partnership”) were framing the whole study, formulating the questions, etc.

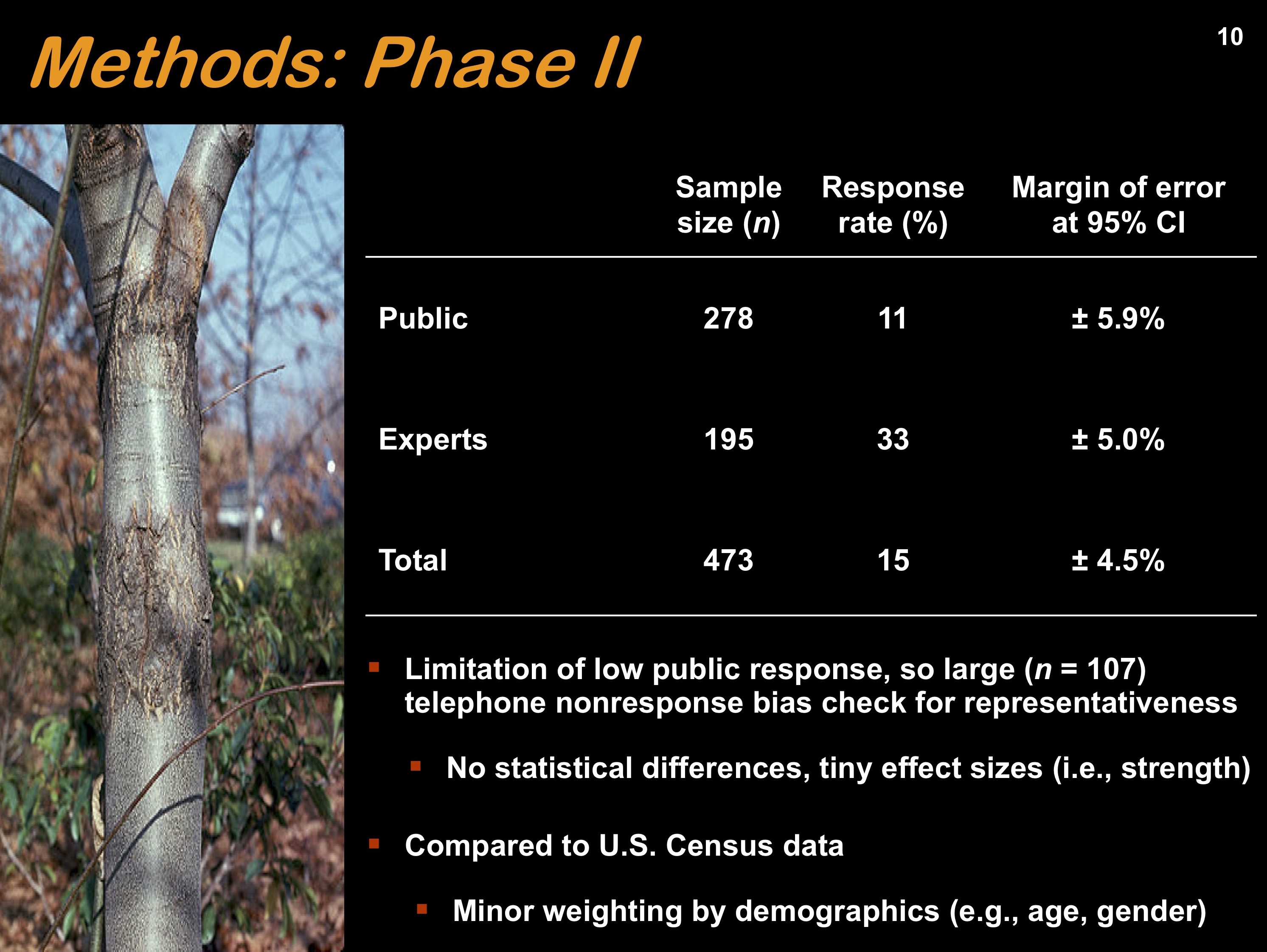

We get to actual statistics on p. 10 (suddenly becoming very hard to read, with white numbers on a very light background). The study is based on 278 responses from the general public (which is sometimes subdivided into two groups: those from counties with chestnut trees and a nationwide public) and 195 from “experts”. These are very small sample sizes. For comparison: The New York Times always uses samples of over 1,000 for testing even for simple issues, e.g. outcomes of elections. Apart of this, the last column of the table on p.10 is quite confounding: The margin of error at given significance level normally refers to testing for a single parameter. In the present situation we are dealing with multiple hypothesis testing. So the meaning of the figures is not clear. The authors ignore the problem and give no indication as to what they mean. They also ignore that a good statistical analysis would not only talk about significance but also about power and the effect of multiple testing on power. The notes below the table are unclear; this kind of producing numbers without saying what they refer to occurs in other parts of the study as well.

“Results” begin to appear on p.14. They show that the public’s (both the general and the chestnut county public’s) attitude to genetic modification is negative in response to climate change or increased forest growth and (at least in the affected counties) positive in response to chestnut blight. This is fairly well confirmed by the table on p. 15 (“How would you vote?”) according to which the vote for genetic modification by the nationwide part of the general public would be 43%, 45%, and 53%, respectively.

On this same table values for the chi^2 test are given. In this rather complicated setup there are more than one ways to apply this test. No indication about that is given, and no explanation to the general reader of what it means. – Actually, after seeing the data, it is not very important.

The conclusion drawn on p. 16 is that there is more support for genetic modification for one purpose than for the other two purposes being discussed. Nothing is said about whether this support is strong or weak or non-existent, and what it is in the three groups considered. The conclusion, as far as it goes, is correct, but of no relevance as to whether the general public supports or opposes genetic modification.

The next question is about six possible interventions against chestnut blight, three of them being various forms of genetic manipulation. The test results are rather confusing. According to p. 19 the public’s (both subgroup’s) attitude to all three forms of genetic intervention is negative. But as to the question of “How would you vote” (p. 20) there are small majorities voting for, rather than against, two of the three kinds of genetic intervention. The “conclusion” (p.21) mentions only this, and not the negative “attitude”. Taken as a whole the conclusion is therefore incorrect.

After this there are results about how value systems (environmental, political, etc.) and specific knowledge influence attitudes. Furthermore, (using sample populations different from that of the main study) an investigation about how accompanying the questionnaire with scientific information (not specified), and “framing” (by including bogus statements for resp. against) influence the results. – It is seen that framing has a very high effect.

At the end (p. 39): “Next steps” include finishing the analysis of collected data and issuing a final report planned for January 2017. These do not seem to have become available.

To summarize, in the technical analysis of the data there are indications of serious flaws and there is a lack of information about the methods used. The sample sizes are definitely too small. Most importantly, the design of the study, as well as the presentation of its results, show a built-in bias favoring intervention using genetic technology in forestry.

Adam Koranyi.